The second article in our 2020 series, Remembering our Societal Stabilizers was written by IIHS Advocacy Associate, Eduardo Padron, at the beginning of the year. While much has changed since then, the message is as relevant and clear now as it was on the day it was written and we urge the world not to forget the threats facing human security that existed before the pandemic and continue to persist today. We invite you to engage with this stabilizer and consider what steps we ought to take in order to move towards security for all as we go into 2021.

The 2020 link: modern-day slavery

One of the major successes of international feminism from the 1990s to the present day has been transforming the human rights discourse from a gender-neutral frame to one that acknowledges the unique vulnerabilities faced by women. Most international actors are already aware of how women are often the worst victims of violence. Women, migrants, and victims of modern-day slavery are all directly interconnected through one crucial factor: the way they experience insecurity and the conditions that must be met for them to be secure.

Girls and women experience human insecurity differently from men and are subject to gender hierarchies and power inequities that work to undermine their safety. This is partially caused by their lower socio-economic status in society, which makes it difficult for them to articulate and act upon their security needs. As women are often involuntary victims of conflicts and crises, they have an important stake in building a culture of peace where two essential issues must be addressed. First, the fact that no permanent foundations of peace and development can be built without the full participation and empowerment of women. Secondly, the importance of the education of girls and women as a key factor for such empowerment must be considered.

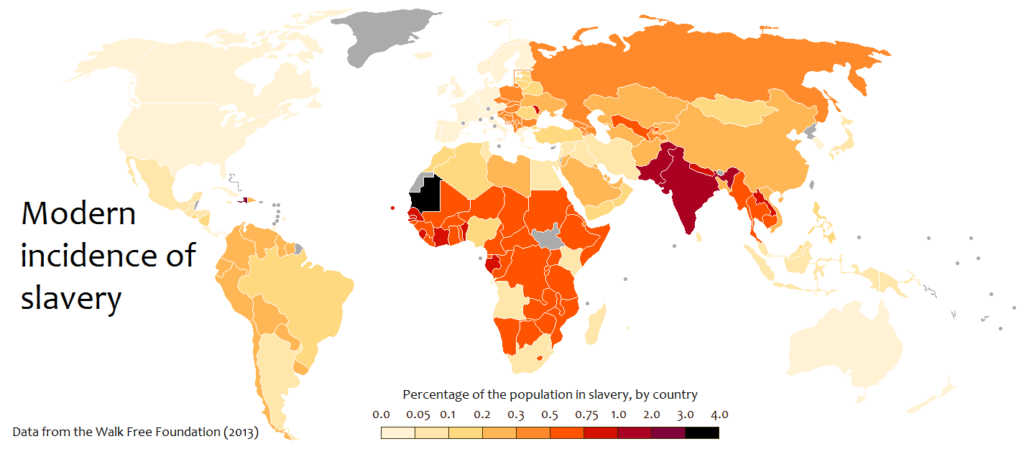

Their insecurity is exacerbated when the authority of a state and society is unable to protect them. It is under these circumstances that they are more vulnerable to experiencing slavery in any of its forms: domestic work, work within the sex industry, and also forced marriage, which together represents 99% of victims of forced labor. The Global Estimates of Modern Slavery confirms women and girls are disproportionately affected by modern slavery, accounting for 28.7 million, or 71 percent of the overall total of enslaved persons.

Defining human trafficking

The United Nations defines human trafficking as the recruitment, transfer or harboring of persons through force or deception for the purpose of exploitation. Unlike migration, which is a voluntary movement of a person from one country or area to another. Article 3 (a) of smuggling protocol defines the following, “smuggling of migrants shall mean the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefits, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident.” On the other hand, trafficking is a movement by deception or coercion. All acts of trafficking involve migration but not all acts of trafficking are migration. If migration is not accompanied by coercion or deception and does not result in forced labor or slavery-like conditions, it is not trafficking.

The case of Nepal: from sex trafficking to forced labor

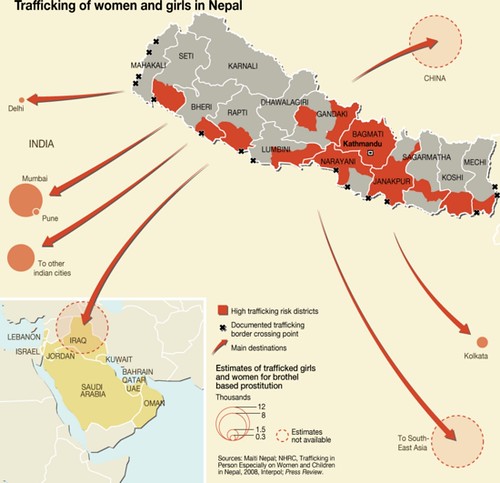

Thousands of women and girls from Nepal are trafficked into India each year, and many are forced into sex work. The government is aware of the problem but interventions have been too minor to be effective. The most obvious solution may be the hardest: creating opportunities at home so people don’t want to go abroad. On account of difficult economic conditions and a lack of resources, women are more easily targeted. Once trafficked abroad and working for “owners” they are required to do any kind of labor, whether that be household work or being sexually abused.

Image: Wikimedia Commons | Street in Kathmandu

In Nepal, male family members are prioritized for receiving an education, job, or for training in various sectors. That leaves women and girls in a particularly vulnerable position. Nepal’s primary economic activity is agriculture, however, many women are unable to find agricultural jobs, or in fact any work in rural areas at all. This is cited as a key motivating factor for encouraging migration and only makes this group more vulnerable to being caught and trafficked by mafia networks. It is worth noting that Nepal has long been a nation of migrant workers, with remittances from abroad fueling almost one-third of its GDP. That money has been necessary to support a local economy dragged down by the lack of a manufacturing base and declining agricultural production. After migrating and under severe conditions of poverty, a person is often compelled to do any kind of work for their livelihood and survival.

The lack of opportunities resulting from poverty, marginalization, and subsequent forced displacement creates the perfect breeding ground for trafficking mafias. Nepal is the fifth-lowest Asian country on the Human Development Index (HDI) scale, where a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line. It is a nation particularly vulnerable to trafficking and the problem is compounded by the permeability of its land borders with India and China. Mafias mainly use open borders with India to exploit those in brothels in Calcutta or New Delhi, or as a route to sell them later in the Middle East.

Image: Flickr

However, India is not the final destination of all Nepalese trafficking victims. Women and girls have been rescued from a whole host of countries beyond South Asia, including Hong Kong, Malaysia, China, and Russia, according to NGOs and government officials. In many cases, the exact nature of the transactions is hidden from local recruiters, who really do think they’re finding women jobs as domestic workers in the Middle East. In the vast majority of cases, anti-trafficking activists say the local recruiter does not know where a victim will end up.

Finding solutions

The government of Nepal has demonstrated mixed anti-trafficking efforts. Authorities have prosecuted public officials accused of being involved in fraudulent recruitment however only a small number of traffickers have been convicted. Nepal has prohibited many, but not all forms of human trafficking through the 2007 HTTCA (Human Trafficking and Transportation Control Act) and the 2008 regulation (Human Trafficking and Transportation Control Rules).

Image: Unsplash | Woman cooking in rural Nepal

The HTTCA prohibits both internal and transnational trafficking and criminalizes slavery, bonded labor, and the buying and selling of a person. However, it does not criminalize “the recruitment, transportation, harboring or receipt of persons by force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of forced labor”. Additionally, it places more emphasis on sex trafficking than any other forms of human trafficking. As noted by government officials and civil society, the majority of convictions under the HTTCA concerns transnational sex trafficking.

The trafficking of Nepalese women has also increased considerably in other countries where it did not occur in the past. Globalization has enabled trafficking networks to spread to countries as far away as Tanzania, although most cases are concentrated to the Middle East in places such as Iraq or Syria, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait. In the past, traffickers coerced women and girls with promises of a job in India. Now they do the same but send them even further afield.

Visualizing peacebuilding

Clearly, however, it is not enough to prevent women from being trafficked. “You have to offer alternatives to stop [women] being vulnerable,” says Anuradha Koirala, activist and founder of Maiti Nepal. “especially if they [women] have family problems, they will find a second home in the prevention centers that the organization has in various locations in Nepal. Sometimes we also offer services with which they can earn a living.”

Founded in 1993, Maiti Nepal has been instrumental in the capture and imprisonment of 1,571 traffickers, and in the mediation of 10,665 cases of sexual violence. The NGO has also intercepted 36,045 female victims who might be vulnerable to human trafficking. In 2016 alone, it helped prevent 5,700 women from embarking on a coerced journey from home. The majority of these prevented journeys occurred at the border (1,100 in Nepalgunj), but also in other areas where the organization established posts in some of Nepal’s main bus stations.

Image: Unsplash

Large-scale campaigns by the Nepalese government and NGOs have successfully heightened awareness about the risks of migration to those living in many of Nepal’s rural communities. Government-led interventions to actually curb trafficking, however, have been too small-scale to be effective.

Local and national governments are among the key actors in developing a comprehensive anti-trafficking response to all forms of human trafficking from sexual exploitation to forced child labor. The role of national authorities is particularly crucial for the prevention of trafficking, while local authorities play a significant role in addressing the needs of victims. Cooperation among local actors, from city and province authorities to private sectors and non-governmental organizations, is vital to ensure effective victim identification and protection as well as prosecution and conviction of perpetrators.

Through such joint efforts, authorities might be able to meet the needs of victims and help them regain their independence. The government’s commitment to justice has greater impacts beyond maintaining the sanctity of law. Prosecuting and convicting traffickers for their crimes can also have an extremely positive impact on the victim’s recovery process, particularly in overcoming trauma after liberation.